The article was first published in Global Tax Weekly, issue 174. Below is the full text of the eighth article in the series on US taxes for US persons living outside the US.

by Stephen Flott, and Omar Saleh, Flott & Co. PC

This is the eighth article in a series of articles on key US tax compliance and planning issues that should be considered by US executives, entrepreneurs and investors living outside the United States. This article will discuss controlled foreign corporations, deemed income inclusion, and planning opportunities.

Controlled Foreign Corporations And Subpart F Income

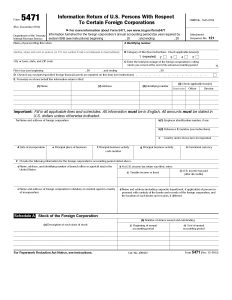

The preceding article of this series (Global Tax Weekly, Issue 170, February 11, 2016) discussed the compliance requirements for IRS Form 5471, specifically with respect to persons who are US shareholders of a Controlled Foreign Corporation (“CFC”). This article addresses CFC and related issues, particularly something called subpart F income.

A foreign corporation is a CFC for a taxable year if more than 50 percent of its stock by vote or value is held by US shareholders at any time during the year.1 If a foreign corporation is a CFC for a period of 30 days or more during a taxable year, then every US shareholder of the CFC at any time during that taxable year and any who own stock in the CFC on the last day of the CFC’s tax- able year must include in gross income his or her share of subpart F income.2 A “US Shareholder” is a US person3 owning at least 10 percent of the voting stock of the CFC.4

US shareholders of foreign corporations are typically not taxed on the earnings of those corporations until they receive distributions, which are usually taxed as dividends, or until they sell their shares. In contrast, for CFC’s there are inclusion rules for certain items of income, which are treated as having been received by the US shareholder even though the CFC does not in fact make any distributions.

In other words, the US shareholder is taxed on income “as if” received when in fact it has not been. The purpose of this inclusion is to prevent the US shareholder from deferring recognition of certain types of income earned through a CFC and thus avoiding or deferring tax on it. The rule can also create an issue for the US shareholder who is expect to pay tax on “phantom” income. In certain circumstances, the rule could result in the US shareholder not being able to pay the tax due. It can also create a timing issue for claiming foreign tax credits on later dividend distributions from the CFC.

To avoid the deemed income inclusion, eleven unrelated US persons could spread ownership to avoid CFC status by each owning an equal interest in the corporation, thus their ownership interest would not meet the minimum 10 percent required to be a US shareholder. This planning could bring other or worse negative tax consequences if the foreign corporation were instead taxed as a passive foreign investment company (“PFIC”). The taxation of PFICs will be discussed in a subsequent article of this series.

The US normally does not tax profits of foreign corporations until they issue dividends to share- holders. If, instead of using a corporation, a US enterprise were to set up a branch (that is, either a partnership or disregarded entity) in a foreign country, the US would tax the US enterprise on the net income generated by the foreign branch.

The goal of allowing US companies to be competitive in the world market through deferral of US tax on income earned through foreign subsidiaries is beneficial; the deferral also creates opportunities for US companies to defer US tax on their foreign earnings. There are countries with no or very low income tax, creating the ability to shift profits to jurisdictions where the US enterprise’s foreign corporations may have few, if any, actual business operations with the result that profits are received in tax favorable countries. This kind of tax planning is usually undertaken for the sole purpose of avoiding US tax.

Say, for example, a US corporation produces widgets in the US for sale in Germany. The sales in Germany are made through a wholly owned German subsidiary corporation. The cost to produce a widget is USD5,000 and each widget sells for USD9,000 in Germany. The US corporation sells the widget to its German subsidiary for USD7,000 and the subsidiary sells it to customers in Germany for USD9,000. Assume the US tax rate is 35 percent and the German tax rate is 25 percent, the sale of the widget would produce an income tax in the US of USD700 (USD2,000 times 35 percent) and an income tax in Germany of USD600 (USD2,000 times 30 percent), for total income tax of USD1,300.

Now assume the US corporation has another wholly owned foreign subsidiary in the Marshall Islands where no production activity occurs. The Marshall Islands has no corporate income tax. The US corporation sells the widget to its Marshall Islands subsidiary for USD5,500, after which the Marshall Islands subsidiary resells the widget to its German subsidiary for USD8,500, and that subsidiary sells the widget to its customers in Germany for USD9,000. The sale of the widget would incur an income tax in the US of USD175 (USD500 times 35 percent), no income tax in the Marshall Islands (USD3,000 times 0 percent), and an income tax in Germany of USD150 (USD500 times 30 percent), for total income tax on the sale of the widget of USD350. By routing the sale through the Marshall Islands, the US corporation’s total income tax drops from USD1,300 per widget to USD525, a saving of USD775.

As illustrated in the example above, if there were no anti-deferral or transfer pricing rules, a US corporation could significantly reduce its taxes on sales in another country by routing the sale first through a wholly owned foreign subsidiary in a no or low tax jurisdiction. The IRS certainly has the ability under Internal Revenue Code (“IRC”) Section 482 to reallocate the income among domestic and foreign affiliates in order to clearly reflect income. The purpose of IRC Section 482 is to allow the IRS to reallocate income according to how unrelated parties would transact with each other under the same facts, also known as the arm’s-length standard. Since there are no concrete rules under IRC Section 482 and almost every transaction will be unique in some aspect, reallocations under IRC Section 482 have proven hard to administer. This is a significant reason Congress enacted subpart F, which denies deferral to certain types of so called “tainted” income earned through a foreign corporation.5

Well after the enactment of subpart F, the Joint Committee on Taxation summarized the purpose of subpart F by stating:

“It has long been the policy of the United States to impose current tax when a significant purpose of earning income through a foreign corporation is the avoidance of tax. Such a policy serves to limit the role that tax considerations play in the structuring of US persons’ operations and investments. Because movable income earned through a foreign corporation could often be earned through a domestic corporation instead, Congress believed that a major motivation of US persons in earning such in- come through foreign corporate vehicles often was the tax benefit expected to be gained thereby. Congress believed that it was generally appropriate to impose current US tax on such income earned through a controlled foreign corporation, since there is likely to be limited economic reason for the US person’s use of a foreign corporation. Congress believed that by eliminating the US tax benefits of such transactions, US and foreign investment choices would be placed on a more even footing, thus encouraging more efficient (rather than more tax-favored) uses of capital.” 6

The above quoted section shows Congress’ initial motivation in enacting the subpart F rules. Congress was concerned with the ability of US companies to transfer income from the taxing jurisdiction of the US for the sole purpose of avoiding US tax.

US shareholders of a CFC must include in their gross income their pro rata share of the CFC’s (i) sub- part F income, and (ii) investment of earnings in US property.7 The US shareholder’s pro rata share is the amount of income the shareholder would receive if, on the last day of its taxable year, the CFC had actually distributed pro rata to all of its shareholders a dividend equal to the subpart F inclusion.8

Since shareholders receive distributions from the earnings of corporations through distributions taxed as dividends, a subpart F inclusion from a CFC is commonly considered a deemed dividend. This is consistent of how a domestic US corporation reports a subpart F inclusion as a dividend on its US tax filing.9 However, for US shareholders who are individuals, subpart F inclusion from a CFC will not qualify as a qualified dividend taxed at preferential tax rates. This is the case even if a distribution from a CFC that is not a subpart F inclusion would receive preferential tax rates as a qualified dividend.

The subpart F income and qualified dividend issue was unsettled for a number of years, with many practitioners believing that subpart F income should be taxed as a qualified dividend, if the other requirements for qualified dividends were met. Since subpart F income was an anti-deferral mechanism and not intended to change the character of the income taxed to the US shareholders, it appeared this would be the proper treatment under the Internal Revenue Code. The inclusion of income under subpart F is also directly related to earnings and profits similar to determining whether a distribution from a corporation is taxed as a dividend. Subpart F inclusions were commonly referred to as “deemed dividends.” The IRS has even issued a number of private letter rulings treating an inclusion under subpart F as a dividend.

In Rodriguez v. Comm’r, 137 T.C. 14 (2011), the Tax Court held that a subpart F inclusion is not a dividend because there is no actual distribution to the US shareholders.10 The Tax Court in their opinion, quoting from a Supreme Court case, states that a “distribution” entails a “change in form of … ownership” of corporate property, “separating what a shareholder owns qua shareholder from what he owns as an individual.”11 The Tax Court reached its conclusion by literally interpreting the rules that apply to subpart F income based on the plain meaning of the statute, and not relying on legislative history for the treatment of subpart F inclusions.

It is important to go through which items constitute subpart F income even though it can seem like a shopping list. A general understanding of what is included in subpart F income will allow a US shareholder to better understand the US tax consequences of investing in a CFC.

Subpart F income includes the following income derived by a CFC:

- Insurance income;

- Foreign base company income;

- International boycott income;

- The sum of any illegal bribes or kickbacks paid by or on behalf of the CFC to a government employee or official; and

- Income from disfavored foreign

A CFC’s subpart F income for its taxable year cannot exceed the CFC’s current year earnings and profits.12 Subpart F inclusion is determined prior to any reduction of current year earnings and profits for dividend distributions.

Subpart F income includes any income attributable to issuing or reinsuring any insurance or annuity contract for a risk located outside the CFC’s country of incorporation. Premium payments and other insurance activities provide an easy opportunity to shift the income to another jurisdiction to avoid US tax. A US corporation could easily shift income by forming a foreign subsidiary in a no or low tax jurisdiction and then reinsuring part of the risk to the foreign subsidiary. The US corporation would then deduct the premiums paid to the foreign subsidiary against its US income and the foreign subsidiary would recognize the premium income at much lower tax rates.

Foreign base company income consists of four additional subgroups of income derived by a CFC. Foreign base company income includes:

- Foreign personal company income;

- Foreign base company sales income;

- Foreign base company services income; and

- Foreign base company oil-related

The taxable amount of foreign base company income is the gross amount of such income, less any deductions properly allocable to such income, including foreign income taxes.13

Foreign personal company income generally includes (i) dividends, interest, royalties, rents and annuities; (ii) net gains from the disposition of property that produces dividend, interest, rent and royalty income; and (iii) net gains from commodity and foreign currency transactions. There are numerous rules that exempt select categories of income from foreign personal company in- come. One important exception is worth mentioning: dividends, interest, rents and royalties received from a related CFC are exempt from subpart F income, provided the payments are not themselves subpart F income of the related CFC. This exception allows cross-border payments between related CFCs without creating subpart F income in the US shareholders.14

Foreign base company sales income includes any gross profit, commissions, fees or other income derived from the sale of personal property. To constitute foreign company sales income, the following requirements must be met:

- The CFC purchases the property from or sells the property to a related person;

- The property is manufactured, produced, grown or extracted outside the CFC’s country of incorporation by an entity other than the CFC; and

- The property is sold for use, consumption or disposition outside the CFC’s country of

The purpose of this rule is to preclude the use of an intermediary foreign corporation in a jurisdiction where neither the manufacturing nor the property is sold for use. In these circumstances it is more likely the intermediary jurisdiction was chosen to avoid US tax. There is another subset of tests to determine whether a CFC manufactured or produced a good within the country of incorporation.

Foreign base company services income includes compensation, commissions, fees or other income received for the performance of technical, managerial, engineering, architectural, scientific, skilled, industrial, commercial and like services, where the CFC performs the services for or on behalf of a related person and the services are performed outside the CFC’s country of incorporation. The policy again is that since the services are being performed outside the country of incorporation, the location of the personal services CFC was more likely selected for the purpose of tax avoidance.

Foreign base company oil income includes foreign source income derived from refining, processing, transporting, distributing or selling oil and gas or primary products derived from oil and gas.

This does not include oil related income of a CFC from sources within a foreign country where the oil or gas is extracted or used.

There are four special inclusion and exclusion rules from subpart F income. First, there is a de minimis rule where gross insurance and foreign base company income is not included as subpart F income for the taxable year if the sum of the gross insurance income and gross foreign base company income for the taxable year is less than both USD1m and 5 percent of the CFC’s total gross income for the year. This is an important exception for multinational companies operating in foreign countries where their only subpart F income is passive types of income, as this exclusion would typically preclude interest income from the CFC’s foreign bank account from being deemed income to the US parent corporation. Of course, for a large foreign subsidiary, the interest income could exceed the de minimus exclusion limits.

There is a full inclusion rule where the CFC’s gross income is treated as subpart F income if the sum of the CFC’s gross insurance income and gross foreign base company income for the taxable year exceeds 70 percent of the CFC’s total gross income for the year; the policy here being that the CFC subpart F income is such a high percentage of the total CFC income that the entire gross income of the CFC will be treated as subpart F income.

There is also an elective high-tax rule where a US shareholder of a CFC can elect to exclude from subpart F income any insurance or foreign base company income that is subject to foreign tax at an effective rate exceeding 90 percent of the maximum US tax rate. The reason for this exception is there would be little to no US tax for the US to collect after applying foreign tax credits. US shareholders with common sense would not avoid US tax by sending their investments to a higher tax jurisdiction. Under these circumstances there is clearly a non-tax motive for the US shareholder to invest in the foreign country.

The last exception is that if the CFC’s subpart F income is effectively connected to a US trade or business then the income is excluded from subpart F income. The reason for this is that this income will be currently taxable in the US at marginal rates. The exception does not apply if the income is exempt from tax in the US or subject to a reduced tax rate under an applicable treaty.

The final category of subpart F income is for the CFC’s investment earnings in US property. The reasoning behind this rule is that a CFC’s investment of earnings in US property can be substantially equivalent to a dividend to its shareholders. Instead of making a dividend distributions to the US shareholder, the CFC could instead loan the amount to the US shareholder. The goal here would be that a loan would not trigger a shareholder level tax as would be the case with a dividend. Under this rule, the amount of the loan will be an income inclusion.

For this purpose, US property includes debt obligations, certain receivables, stock, tangible property and intangibles. Investments with unrelated US parties are excluded as well as legitimate investment purposes for the investment in US property. The goal of the rules are to balance legitimate business purposes of the CFC investment in US property with the opportunity for disguised dividend distributions in relation to the CFC’s US shareholders.

As important for US corporations to be competitive in the international market place is their ability to offset CFC deemed income inclusions with foreign tax credits for income taxes paid to a foreign country. Without special rules for the foreign tax credit, this income would be doubled taxed, placing the US corporation’s operations in foreign countries through a CFC at a tremendous disadvantage to their local competitors. This rule also more closely equates to the tax treatment of US corporations operating in foreign countries through foreign subsidiaries with those operating through a foreign partnership or disregarded entity. This allows US corporations to choose to operate through a foreign corporation or foreign partnership/disregarded entity for reasons other than US tax consequences.

Only US corporations can claim a deemed paid foreign tax credit for income taxes paid by the foreign corporation. The deemed paid foreign tax credit is not available to US shareholders who are individuals or entities other than a corporation. In order for a US corporation to claim a deemed paid foreign tax credit, it must own 10 percent or more of the voting stock of the foreign corporation and receive a dividend distribution. Requiring a dividend distribution from the foreign corporation matches the deemed paid foreign tax credit with a taxable event in the US.

The basic rule is quite simple: to the extent a US corporation receives a dividend from a foreign corporation in which it owns 10 percent or more of the voting stock, the US corporation receives a deemed paid foreign tax credit related to the foreign income taxes paid by the foreign corporation on that income. An issue that arises with the deemed paid foreign tax credit is determining whether a US corporation is taxable on a distribution from a foreign corporation as a dividend.

Ordinarily, a foreign corporation’s earnings and profits available for distribution as dividends are reduced by any foreign taxes paid on the earnings and profits. This creates the anomaly that the US corporation would receive a foreign tax credit for undistributed earnings while the earnings and profits themselves, which determine whether the distribution from the foreign corporation is taxable as a dividend to the US taxpayer, would later be reduced by the same amount of foreign taxes when they are actually paid by the foreign corporation. To prevent this double tax benefit of both a deemed foreign tax credit and deduction from earnings and profits in the same amount, the US corporation must gross up its dividend by the amount of the deemed tax credit.

Another complication of the deemed paid foreign tax credit and the matching of income and taxes requirement is allocating deemed paid taxes to dividend distributions. If the foreign corporation simply paid all of its earnings out every year the allocation of deemed paid foreign tax credits would not be an issue. In contrast, where a foreign corporation accumulates earnings over a number of years, the allocation of deemed paid foreign tax credits is more important. The al- location of deemed paid foreign tax credits is more significant where the tax rate in the foreign country increased or decreased during the period the foreign corporation accumulated earnings.

Under the old rule, a US corporation allocated deemed paid foreign tax credits on a ‘last in first out’ basis. Congress felt that this method allowed bunching of income of the foreign corporation income and in turn allowed the US corporation an opportunity to maximize their deemed paid foreign tax credits.

For post 1986 foreign income taxes, the pooling method is required to allocate deemed paid foreign tax credits. Under the pooling method, post 1986 undistributed earnings of a foreign corporation are computed at the end of the taxable year in which the foreign corporation has made a distribution to the US corporation. The post 1986 undistributed earnings equal the aggregate amount of the foreign corporation’s undistributed earnings and profits for taxable years commencing after December 31, 1986. This amount is reduced by actual dividend distributions from prior taxable years and for any subpart F income previously included in the US corporation’s income. The foreign corporation’s post 1986 income taxes for the deemed paid taxes equals the aggregate amount of the foreign corporation’s foreign income taxes for taxable years starting after December 31, 1986. This amount is reduced by the amount of foreign income taxes related to prior year dividend distributions and subpart F inclusion.

Under the pooling method, the foreign corporation’s post 1986 foreign income taxes are multiplied by the ratio of the current year dividend to the foreign corporation’s post 1986 un- distributed earnings. As compared to the last in first out method, the pooling method evenly allocates the post 1986 foreign corporation’s income taxes in proportion to the post 1986 undistributed earnings.

Without special US tax accounting rules, subpart F income that is included in a US shareholder’s income prior to receiving a distribution from the CFC could create a second layer of US tax when the CFC later distributes the same earnings out to the US shareholder. Under US tax law, it is correct that in order for US shareholders to determine the US tax consequences of their CFC interest, either the CFC or one of the US shareholders will have to keep US tax books for the CFC to determine the appropriate taxation of distributions to US shareholders and for US shareholders that are corporations, the amount of deemed foreign tax credits paid.

The first rule is that a US shareholder can exclude from income distributions of a CFC’s earning and profits that were previously subject to US tax by reason of a subpart F inclusion.15 This tracing rule requires additional items to be tracked in the CFC’s US tax books. There is an ordering rule in tracking previously taxed income for this purpose. Previously taxed income of a CFC is traced first to previously taxed earnings and profits for subpart F income attributable to an investment in US property and then to other subpart F income. If there are remaining earnings and profits after tracing the distribution to previously taxed income, the distribution will be taxed as a dividend to the US shareholder. This portion of the distribution can be taxed as a qualified dividend to US shareholders who are individuals. Since a US shareholder would have already received a deemed paid foreign tax credit at the time of the subpart F inclusion, a US shareholder cannot receive a deemed paid foreign tax credit on distributions that are treated as previously taxed income.

An issue similar to that of double taxation of previously taxed income could occur if US share- holders sold their stock prior to recouping their subpart F inclusion through previously taxed income distributions from the CFC. To prevent disparate treatment on a stock sale, at the time there is a subpart F inclusion, US shareholders increase their basis in CFC stock by the amount of any subpart F inclusion.16 This adjustment prevents double inclusion of the same income through a stock sale. To prevent potential double benefits to the US shareholder when a CFC makes a distribution of previously taxed subpart F income, US shareholders must reduce their stock basis in CFC stock by the same amount.17

In determining the US taxation of a CFC’s earnings, ordering rules for the type of income deemed to be distributed are important. The distribution from a CFC of current year earnings and profits are deemed to be first distributed from subpart F income, then dividends, and then from the CFC’s investment in US property. The application of these two inclusionary rules are separated by dividend distributions, which makes careful US tax accounting important for the US share- holders of the CFC.

Changes in currency rates can create unexpected foreign currency gains or losses on subpart F inclusions to US shareholders. Since CFCs will generally keep their financial records in local currency, it is likely the financial records will not be kept in US dollars, and the subpart F inclusion will need to be converted to US dollars. If the currency exchange rate fluctuates between when the subpart F inclusion occurs and when previously-taxed earnings and profits are distributed or stock is sold, the US shareholder will recognize a foreign currency gain or loss.

Earnings and profits are key in determining a US shareholder’s subpart F inclusion. It is important to remember in tracking US shareholders’ subpart F inclusions that their subpart F inclusions are limited to current earnings and profits. Therefore, it is important to track both current and accumulated earnings and profits, and to remember that there can be no subpart F inclusion related to accumulated earnings and profits.18

The rule is different for inclusion associated with a CFC’s investment in US property. The inclusion is limited to the sum of the CFC’s current and accumulated earnings and profits. Again, this will require additional tracking of the CFC’s US tax accounting.19 As with the reporting of most foreign source income, the earnings and profits of a CFC are computed in conformance with reporting for US corporations, which will require the CFC to make adjustments to its profit and loss statement for US GAAP and then for US tax accounting.20

If a CFC accumulates earnings that are not taxed to US shareholders as subpart F income or as earnings invested in US property, then US shareholders are generally taxed on their share of the accumulated earnings as dividends and not as long term capital gains when the US shareholders sell their stock. Under IRC Section 1248, gain on a US shareholder’s disposition of CFC stock is treated as dividend income to the extent that the earnings and profits attributable to the stock were accumulated while the US shareholder held the CFC stock.

For individual US shareholders, the re-characterization of capital gain income as dividend income under IRC Section 1248 should not have a significant impact if the CFC is located in a country that has a comprehensive income tax treaty with the US because dividends can still qualify as qualified dividends taxed at the same rates as long term capital gains. If the CFC is located in a non-treaty county, then the re-characterization as dividend income will result in the gain on the stock sale being taxed as an ordinary dividend, which is taxed at higher rates. Another issue with the re-characterization as a dividend is that capital losses cannot offset the gain recognized on the sale of CFC stock to the extent the gain is re-characterized from a long term capital gain to dividend income.

The IRC Section 1248 re-characterization can be beneficial for US shareholders that are corporations, as the dividend reclassification on the sale of the CFC stock allows for deemed paid foreign tax credits for income taxes paid by the CFC. The additional deemed paid foreign tax credits can be a significant benefit for corporate US shareholders in reducing their US tax liability.

While the classification of a foreign corporation as a CFC can create negative tax consequences for US shareholders due to the deemed income inclusion rules, there are opportunities to minimize this issue or at least to not compound the issue by recognizing the same income twice for US taxation. The US tax accounting adjustments discussed above in the context of subpart F income included in US shareholders’ income eliminate the possibility that the same income will be taxed twice when earnings are later distributed to US shareholders. Too often these accounting adjustments are missed or overlooked, resulting in US shareholders being taxed on the same income twice. Nobody wants that outcome.

ENDNOTES

1 IRC Section 957(a).

2 IRC Section 951(a)(1).

3 A US person is a US citizen, resident or domestic corporation, partnership, trust or estate.

4 IRC Section 951(b).

5 “Subpart F” refers to IRC Sections 951-965.

6 Staff of Joint Comm. On Tax’n, 99th Cong., 2d Sess., General Explanation of the Tax reform Act of 1986 at 964-965 (Comm. Print 1987).

7 IRC Section 951(a)(1).

8 IRC Section 951(a)(2).

9 US corporations report subpart F inclusions as dividends on line 4 of Form 1120.

10 Rodriguez v. Comm’r, 137 T.C. 14 (2011).

11 Comm’r v. Gordon, 391 US 83, 90 n. 5 (1968).

12 IRC Section 052(c)(1)(A).

13 IRC Section 954(b)(5).

14 IRC Section 954(c)(6).

15 IRC Section 959(a).

16 IRC Section 961(a).

17 IRC Section 961(b).

18 IRC Section 952(c)(1)(A).

19 IRC Section 956(a)(2).

20 Reg. Section 1.964-1(a)(1).